Buddhism and the Production of Buddhist Art in Korea Was Greatly Supported by

Buddhism, in Korean Bulgyo, was introduced by monks who visited and studied in Prc and then brought back diverse Buddhist sects during the Iii Kingdoms menses. It became the official country religion in all Iii Kingdoms and subsequent dynasties, with monks ofttimes belongings important informational roles in governments. Korean Buddhism came to be much more inclusive than in other cultures with pregnant attempts made by important Buddhist scholars to reconcile the many diverging branches of the faith. Buddhism would accept a profound influence on Korean art, literature, and compages from bells to pagodas, ceramics, sculpture, and even developments in printing techniques.

Introduction From China

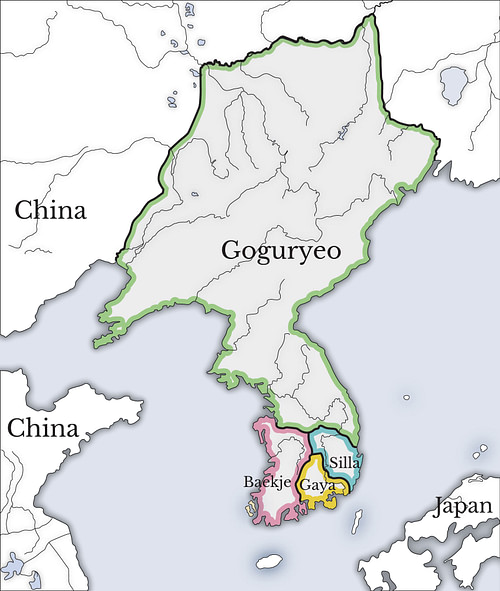

According to tradition, Buddhism was introduced first to the kingdom of Goguryeo (Koguryo) in 372 CE, followed by Baekje (Paekche) in 384 CE, and finally in the Silla kingdom between 527 and 535 CE. The first monk to bring Buddhist teachings was Sundo, who was sent for that purpose by the ruler of Eastern Qin, Fu Jian. It was hoped that stronger cultural ties with Goguryeo would pb to more than practical cooperation in meeting the military machine threat posed past hostile Manchurian tribes. A decade later, Marananta, an Indian or Serindian monk, came from the Eastern Jin state and taught Buddhism in the Baekje kingdom. In both states, the new faith received a favourable reception. In the Silla kingdom, though, Buddhism was seen as a threat to the traditional religions of shamanism, animism, and ancestor worship, and not until the martyrdom of the monk Ichadon was Buddhism finally accepted and and then promoted by the royal court.

Unified Silla Kingdom Gold Buddha

Political Endorsement

The Korean states probable adopted Buddhism and other aspects of Chinese culture as a mode to ingratiate themselves with their powerful neighbour. Yet in their infancy, the Three Kingdoms faced incursions from Manchurian tribes, each other, and the latent threat of further Chinese expansion into the peninsula when they already held commanderies in the north. Korea, naturally, had its own indigenous culture and typically added its own postage stamp of identity to those influences which came from away, but yet, ideas on religion, authorities, courtroom rituals, language, tomb architecture, ceramic product, sculpture, coinage, and classic literature all came from Mainland china. Korean states, in their plow, would spread Buddhism, and some of these other features of civilisation, to Japan. Korean monks would also keep to travel to China in the following centuries in order to acquire new noesis, texts, and discover new branches of the religion.

In that location were other advantages for Korean rulers to promote Buddhism besides keeping good relations with China. Equally most monks came from the elite, the religion became an endorsement of the status quo and gave rulers a certain prestige of association. Many monks became advisors to monarchs over the centuries, giving governments actress authority in the optics of the people. As the historian Jinwung Kim summarises,

The Buddhist teaching of an endless cycle of reincarnation, a rebirth based on karma, retribution for the deeds of a former life, justified strict social stratification. Buddhism was a doctrine that justified the privileged position of the establishment, and for this reason, information technology was adamantly welcomed past the king, the royal firm, and the aristocracy. (67)

The appeal of Buddhism for the poor was the bulletin that the suffering of this life could be avoided in the next ane but the positions of potency within it were largely reserved for the well-educated scholars who had the time and means to pursue enlightenment. In the Silla kingdom, aloof youths were trained in the Hwarang or 'Flower Boys' system, which despite its Buddhist teachings, emphasised martial prowess and heroism. During the Goryeo dynasty, there were as well archway examinations for monks based on sacred texts, further limiting access past the under-privileged.

3 Kingdoms of Korea Map

Buddhism, although the state organized religion, existed side-by-side with the other three main religions practised in Korea: Confucianism, Shamanism, and Taoism. Confucianism was largely observed in the realm of government, merely the others remained popular with the lower classes, and in that location was besides much borrowing of iconography in the arts with Buddhist paintings incorporating shamanistic elements and gods, and vice-versa. Even so, Buddhism, with its country-backing, was made ever more popular, especially past the rulers of the Goryeo dynasty, starting with their founder Wang Geon (aka Taejo, r. 918-943 CE) who credited his success in defeating Goryeo's enemies to his faith in Buddhism:

The success of the neat enterprise of founding our dynasty is entirely owing to the protective powers of the many Buddhas. We must therefore build temples for both Son and Kyo Schools and appoint abbots to them, that they may perform the proper ceremonies and themselves cultivate the way. (Portal, 81)

In one case established as the official state religion, Buddhist temples and monasteries sprang up beyond Korea, and these, with their landed estates, regal patronage, and exemption from tax, became so wealthy that the whole religious apparatus rivalled that of the state itself. Many such monasteries even had their own military recruited from warrior-monks and the general populace. It is also truthful that such institutions helped the poor past offer regular feasts and accommodation to those in dire straits.

The true-blue would recite sutras, lite incense sticks, & walk around the pagoda of a temple.

Rites, Rituals & Festivals

Buddhist temples may have 1, three, or five main halls and these business firm statues (or sometimes just paintings) of Buddha or Bodhisattvas (beings which refrain from joining nirvana in order to assist the living) which receive worship, prayers, and dedications from devotees. The faithful would recite sutras (the sermons of Buddha), light incense sticks, and walk effectually the pagoda of a temple. Such rites tend to be performed past the individual rather than congregations of believers. Important festivals in the calendar, when group activities did occur, included the Buddha'due south birthday (chopail) when worshippers visited temples in lantern-lit processions while chanting mantras and hung paper lanterns in their homes and in the streets. Another major festival was Palgwanhoe or the 'Eight Vows Festival' which commemorates departed spirits and was linked to the harvest in farming communities.

Developments in Korean Buddhism

As Buddhism evolved in China with the creation of diverse sects, so too in Korea the faith branched out, either from straight false via travelling monks such as Beomnang who brought back Seon (Zen) Buddhism in the offset half of the 7th century CE, or through Korea'due south own accommodation. The monk Uicheon (1055-1101 CE) famously attempted but ultimately failed to bridge the gap betwixt the two major branches of Buddhism – the Son and Kyo sects, which stressed the importance of meditation and scriptures respectively. Jinul (1158-1210 CE) was more than successful in this effort, epitomised past his famous maxim: 'sudden enlightenment followed by gradual cultivation.' Jinul's unifying and inclusive class of Buddhism is known as Jogye Buddhism, and it became the official state religion of Korea with its middle at the Sonnqqwangsa temple near modern-day Sunchon. From the 15th century CE, Buddhism would be replaced in importance by the ascent of Neo-Confucianism, at least in terms of land endorsement. Jogye Buddhism continues today in South korea to be the most popular form of Buddhism.

Jinul

Buddhist Art

Buddhism in Goryeo Korea was direct responsible for the development of printing for it was to spread Buddhist literature that woodblock press improved and and then movable metal blazon was invented in 1234 CE. Indeed, the entire corpus of Buddhist texts, the Tripitaka, was printed in 1251 CE using over 80,000 woodblocks, partly in the belief that this would help protect Korea from Khitan invasions. Another Buddhist contribution to the arts is illuminated manuscripts. These sagyong are usually of texts from the sutras (sermons) attributed to Buddha and formed scrolls and folded books. They were written past monk-scribes on indigo hanji paper using brilliant dyes and sometimes even silver and aureate. Buddhist monks also painted frescoes and silk wall hangings to decorate temples, with bodhisattvas and water-flowers beingness the most popular subjects.

The entire corpus of Buddhist texts, the Tripitaka, was printed in 1251 CE using over fourscore,000 woodblocks.

Rock and gilt-statuary sculptures were produced, especially of the Buddha, bodhisattvas, and the futurity Buddha, Maitreya. Figures of Buddha equally Maitreya (the coming Buddha) were pop and some are massive such as the 17.4 metre (57 ft.) loftier one at Paju and the 18.4 metre (59.3 ft.) tall figure at the Kwanchok temple in Nonsan which were both carved out of natural boulders in the 11th century CE. Another expanse of metalwork was the product of bells for Buddhist temples in both the Unified Silla and subsequent Goryeo kingdom. These and pottery used Buddhist motifs such equally the lotus blossom, cranes, and clouds. Finally, Buddhism was an of import subject area in hyangga, the poetical 'land songs,' which were written in the Silla and Goryeo kingdoms.

Buddhist Architecture

Buddhist temples were built in dandy numbers across the peninsula, but the 7th-century CE Miruk temple at Iksan (at present lost) is worth special mention. Built by the Baekje king Mu, it was the largest Buddhist temple in East asia and had two stone pagodas and ane in woods. I stone pagoda survives, albeit with only six of its original 7-9 storeys. The just other surviving Baekje pagoda is also of stone and located at the Chongnim temple at Buyo. Rock pagodas are Korea's unique contribution to Buddhist architecture (in Nihon they are of wood and in Communist china of brick).

Dabotap Pagoda, Gyeongju

Notable surviving Buddhist structures at Gyeongju, the Silla capital, include ii more surviving stone pagodas – the Dabotap and Seokgatap – which both date to the eighth century CE, traditionally 751 CE. This pair was originally role of the magnificent 8th-century CE Bulguksa temple ('Temple of the Buddha Land'), which now stands restored merely but a fraction of its original size. The circuitous, as its name suggests, was designed to stand for the Land of Buddha, that is paradise. For this reason, there are three principal zones: Birojeon (Vairocana Buddha Hall), Daeungjeon (Hall of Bang-up Enlightenment and main temple), and Geungnakjeon (Hall of Supreme Bliss). This architectural representation of paradise, which rises symmetrically from a lotus lake, is symbolically entered via 2 stone bridges and a big staircase, reminding the company that they are leaving the earthly realm behind them and stepping into the sacred realm of Buddha.

One of the outstanding Buddhist structures from the Unified Silla menstruum is the Buddhist cave temple at Seokguram due east of Gyeongju. Constructed betwixt 751 and 774 CE, it contains a circular domed inner chamber within which is a massive iii.45-metre-loftier seated Buddha. The walls are decorated with 41 large figure sculptures of disciples and bodhisattvas.

A good idea of the architectural fashion prevalent during the after Goryeo dynasty (918-1392 CE) is seen in the 13th-century CE Hall of Eternal Life (Muryangsujeon) at the Buseoksa temple in Yeongju. It is one of the oldest wooden structures surviving in the whole of Korea.

This content was made possible with generous support from the British Korean Society.

This article has been reviewed for accuracy, reliability and adherence to academic standards prior to publication.

Source: https://www.worldhistory.org/article/973/buddhism-in-ancient-korea/

0 Response to "Buddhism and the Production of Buddhist Art in Korea Was Greatly Supported by"

Postar um comentário